[Note: A condensed and revised version of this article was published here in The Conversation, an online forum of academic research headquartered in Melbourne, Australia.]

Introduction

What do iPhones, Twitter, Netflix, cleaner cities, safer cars, state-of-the-art environmental management and modern medical diagnostics have in common? They all are made possible by Moore’s Law.

Moore’s Law stems from a seminal 1965 article by Intel founder Gordon Moore. He wrote

The complexity for minimum component costs has increased at a rate of roughly a factor of two per year. … Certainly over the short term this rate can be expected to continue, if not to increase. Over the longer term, the rate of increase is a bit more uncertain, although there is no reason to believe it will not remain nearly constant for at least 10 years. That means by 1975, the number of components per integrated circuit for minimum cost will be 65,000.

Moore noted that in 1965 engineering advances were enabling a doubling in semiconductor density every 12 months, but this rate was later modified to roughly 18 months. In any event, Moore’s Law has now continued unabated for 45 years, defying several confident predictions that it would soon come to a halt, and represents a sustained exponential rate of progress that is without peer in the history of human technology. Here is a graph of Moore’s Law, shown with the transistor count of various computer processors (courtesy Wikimedia):

Present status of Moore’s Law

At the present time, researchers are struggling to keep Moore’s Law on track. Processor clock rates have stalled, as chip designers have struggled to control energy costs and heat dissipation, but the industry’s response has been straightforward — simply increase the number of processor “cores” on a single chip, together with associated cache memory, so that aggregate performance continues to track or exceed Moore’s Law projections.

The capacity of leading-edge DRAM main memory chips continues to advance apace with Moore’s Law. The current state of the art in computer memory devices is a 3-D design, which will be jointly produced by IBM and Micron Technology, according to a December 2011 announcement from IBM.

At the present time, the best bet for the future of Moore’s Law are nanotubes — submicroscopic tubes of carbon atoms that have remarkable properties. According to a recent NY Times article, Stanford researchers have created prototype electronic devices by first growing billions of carbon nanotubes on a quartz surface, then coating them with an extremely fine layer of gold atoms, then using a piece of tape (literally!) to pick them up and transfer them to a silicon wafer. They believe that commercial devices could be made with these components as early as 2017.

Moore’s Law in science and mathematics

So what does this mean for researchers in science and mathematics?

Plenty, as it turns out. A scientific laboratory typically uses hundreds of high-precision devices that rely crucially on electronic designs, and with each step of Moore’s Law, these devices become ever cheaper and more powerful. One prominent case is DNA sequencers. When scientists first completed sequencing a human genome in 2001, at a cost of several hundred million U.S. dollars, observers were jubilant at the advances in equipment that had made this achievement possible. Today, only ten years later, researchers expect to reduce this cost to only $1000 within two years, according to a recent NY Times report, and genome sequencing may well become a standard part of medical practice. This astounding improvement is even faster than Moore’s Law!

Applied mathematicians have benefited from Moore’s Law in the form of scientific supercomputers, which typically employ hundreds of thousands of state-of-the-art components. These systems are used for tasks such as climate modeling, product design and biological structure calculations. As of the current date (1 Jan 2012), the world’s most powerful system is a Japanese supercomputer that recently ran the industry-standard Linpack benchmark test at over 10 “petaflops,” or, in other words, 10 quadrillion floating-point operations per second.

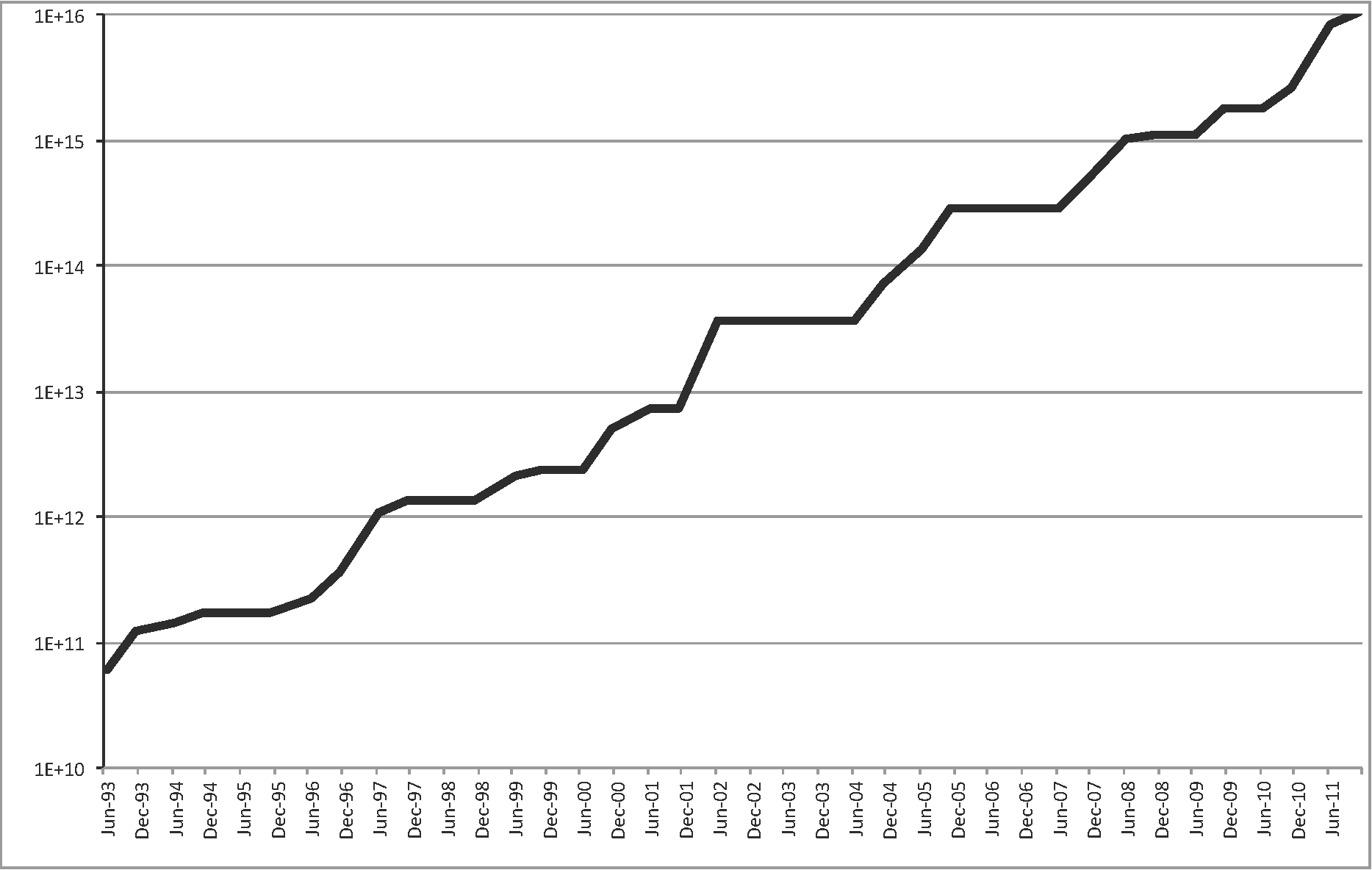

Here is a graph of the Linpack performance of world’s leading-edge system over the time period 1993-2011 (data courtesy Top 500 site). Note that over this 18-year period, the performance of the world’s #1 system has advanced more than five orders of magnitude. The current #1 system is more powerful than the sum of the world’s top 500 supercomputers just four years ago.

Pure mathematicians have been a relative latecomer to the world of high-performance computing. The present bloggers well remember the era, just a decade or two ago, when the prevailing opinion in the community was that “real mathematicians don’t compute.” But thanks to a new generation of mathematical software tools, not to mention the ingenuity of thousands of young, computer-savvy mathematicians worldwide, remarkable progress has been achieved in this arena as well (see our 2011 AMS Notices article on exploratory experimentation in mathematics).

For example, in 1963 Daniel Shanks, who himself had calculated pi to 100,000 digits, declared that computing one billion digits would be “forever impossible.” Yet this level was reached in 1989. In 1989, famous British physicist Roger Penrose, in the first edition of his best-selling book The Emperor’s New Mind, declared that humankind likely will never know if a string of ten consecutive sevens occurs in the decimal expansion of pi. Yet this was found just eight years later, in 1997.

Computers are certainly being used for more than just computing and analyzing digits of pi. For example, in 2003 the American mathematician Thomas Hales completed a computer-based proof of Kepler’s conjecture, namely the long-hypothesized fact that the simple way the grocer stacks oranges is in fact the optimal packing for equal-diameter spheres. Many other examples could be cited.

Future prospects

What does the future hold? Assuming that Moore’s Law continues unabated at approximately the same rate as the present, and that obstacles in areas such as power management and system software can be overcome, we will see, by the year 2021, large-scale supercomputers that are 1000 times more powerful and capacious than today’s state-of-the-art systems — “exaflops” computers (see NAS Report). Applied mathematicians eagerly await these systems for calculations, such as advanced climate models, that cannot be done on today’s systems.

Pure mathematicians will use these systems as well to intuit patterns, compute integrals, search the space of mathematical identities, and solve intricate symbolic equations. If, as one of us discussed in a recent Conversation article, such facilities can be combined with machine intelligence, such as a variation of the hardware and software that enabled an IBM system to defeat the top human contestants in the North American TV game show Jeopardy! (see NY Times report), we may see a qualitative advance in mathematical discovery and even theory formation. Only time will tell for sure, but it is not a big leap to imagine that within the next ten years tailored and massively more powerful versions of Siri (Apple’s new iPhone assistant) will be an integral part of mathematics, not to mention medicine, law and just about every other part of human life.

Some observers, such as those in the Singularity movement, are even more expansive, predicting a time just a few decades hence when technology will advance so fast that at the present time we cannot possibly conceive or predict the outcome. The present bloggers do not subscribe to such optimistic projections, but even if more conservative predictions are realized, it is clear that the digital future looks very bright indeed. We will likely look back at the present day with the same technological disdain with which we currently view the 1960s.

[A version of this article appeared in The Conversation.]