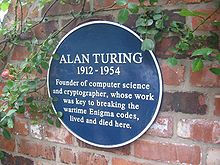

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of famed British mathematician Alan Turing (23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954). The outline of his remarkable life and sad ending has by now become fairly well known. Turing laid numerous foundation stones of modern computing, ranging from the deepest mathematical nature of computing (using what are now called Turing machines he provided the modern approach to incompleteness and undecidability) to specific issues of practical design; he also contributed to mathematical biology (morphology) and much else. At the same time, he played a key role in the British government’s breaking of the German Enigma code at the now-fabled but then ultra-secret Bletchley Park, thus arguably accelerating the end of World War II.

Turing (see http://www.turing.org.uk) was many other things: a world class marathon runner, a troubled homosexual, and an atheist who famously said “The universe is a differential equation. Religion is an initial condition.” Those who knew him savour Feynman-like anecdotes. His achievements are perhaps most succinctly summarized by Harvard scholar Steven Pinker, who declared:

It would be an exaggeration to say that the British mathematician Alan Turing explained the nature of logical and mathematical reasoning, invented the digital computer, solved the mind-body problem, and saved Western civilization. But it would not be much of an exaggeration.

One of Turing’s many signal contributions was a 1950 article that defined what is now known as the “Turning test.” In this article, he proposed a test in which a human “converses” with two entities — one human and one computer program — over a text-only channel (i.e., a computer keyboard/screen), and then attempts to determine which is the human and which is the computer. If, after say five minutes of testing, the majority of human interrogators are unable to determine which is which, Turing said that we could claim that the computer system has achieved a certain level of intelligence.

[Added on 24 Jun 2012:] Alan Turing’s brother wrote some memoirs of Alan’s life. See this report.

Turing’s article even anticipated several possible objections to his test, including mathematical and philosophical objections, which continue to be debated to the present day. For example, some potential questions might not be “fair” to a computer. And we all have human acquaintances who might be judged “computer” in such a test.

In the decades since 1950, when Turing proposed the test, it has been widely influential in directing progress in the computing field in general and in artificial intelligence in particular. Some early attempts at Turing test programs pointed out both the promise and the perils of this enterprise. In 1966, Joseph Weizenbaum created a program, known as ELIZA, which identified keywords in text typed by a human, and then responded with some sort of clever but inquiring response, in the style of a psychologist interviewing a patient. Although some subjects were genuinely surprised to learn that the “psychologist” was a computer, to more skeptical testers its weaknesses quickly became evident. The present authors do remember enjoying playing with it when personal computers first allowed for relaxed therapy sessions.

Progress in the field languished somewhat during the 1970s and 1980s, but since 1991 there has been an annual Loebner Prize in artificial intelligence in which ELIZA’s children — now called “chat-bots” — compete to pass the Turing test. Two recent advances have dramatically enhanced interest: (a) the ready availability of many terabytes of data, from technical documents on every conceivable topic to the growing personal databases of “lifeloggers”; and (b) sophisticated statistical techniques for organizing and classifying this data.

This technology was perhaps most publicly brought to the public eye with the recent defeat of two champion human contestants on the American quiz show “Jeopardy!” by an IBM-developed computer system known as “Watson.” Additional details on Watson (both its Jeopardy! achievement and future commercialization plans) are available from the IBM Watson website and also in a New York Times article. See also our previous blogs on Watson: Math Drudge #1 and Math Drudge #2 and HuffPost article on Games computers play with us.

Watson is now rapidly moving into specializations for medicine and voice recognition among other things. IBM clearly views Apple Computers’ Siri assistant, available with the iPhone 4S, as a main target of competition. Meanwhile Google and AT&T are working on similar systems, according to a recent UK report. Among other things, Watson-type technology offers amazing opportunities as an intelligent assistant for mathematical research.

So far no computer system has passed the Turing test, according to the strict rules of the Loebner prize competition, but they are getting close. The 2010 and 2011 competitions have been won by a chat-bot computer system known as “CHAT-L,” programmed by Bruce Wilcox. In 2010 this program actually fooled one of the four human judges into thinking it was human.

All this raises the question of whether a computer system that finally passes the Turing test is really “conscious” or “human” in any sense. These issues were summarized by Robert M. French in a recent Science article:

All of this brings us squarely back to the question first posed by Turing at the dawn of the computer age, one that has generated a flood of philosophical and scientific commentary ever since. No one would argue that computer-simulated chess playing, regardless of how it is achieved, is not chess playing. Is there something fundamentally different about computer-simulated intelligence?

French is among the more pessimistic observers. Others, such as futurist Ray Kurzweil are much more expansive. He predicts that in roughly the year 2045, machine intelligence will match then transcend human intelligence, resulting in a dizzying advance of technology that we can only dimly foresee at the present time. Kurzweil outlines this vision in his recent book The Singularity Is Near.

Only time will tell when Turing’s vision will be achieved. But civilization will never be the same once it is.

[Added 17 Jun 2012] The results of the 2012 Loebner Prize were just announced. This year, none of the judges were fooled by any of the “bots.” More details are available here.

[A version of this article appeared in The Conversation.]