Pi is very old

The number pi = 3.14159265358979323846… is arguably the only mathematical topic from very early history that is still being researched today. The Babylonians used the approximation pi ≈ 3. The Egyptian Rhind Papyrus, dated roughly 1650 BCE, suggests pi = 256/81 = 3.16049…. Early Indian mathematicians believed pi = √10 = 3.162277… Archimedes, in the first mathematically rigorous calculation, employed a clever iterative construction of inscribed and circumscribed polygons to able to establish that 3 < 10/71 = 3.14084... < pi < 3 1/7 = 3.14285... This amazing work, done without trigonometry or floating point arithmetic, is charmingly described by George Phillips in the Pi Sourcebook (Entry 4).

Pi in popular culture

The number pi, unique among the pantheon of mathematical constants, captures the fascination both of the public and of professional mathematicians. Algebraic constants, such as √2 , are easier to explain and to calculate to high accuracy. The constant e = 2.71828… is pervasive in physics and chemistry, and even appears in financial mathematics. Logarithms are ubiquitous in the social sciences. But none of these other constants has ever gained much traction in the popular culture.

In contrast, we see pi at every turn. In an early scene of Ang Lee’s 2012 movie adaptation of Yann Martel’s award-winning book The Life of Pi, the title character Piscine (“Pi”) Molitor writes hundreds of digits of the decimal expansion of pi on a blackboard to impress his teachers and schoolmates, who chant along with every digit. (Good scholarship requires us to say that in the book Pi contents himself with drawing a circle of unit diameter.) This has even led to humorous take-offs such as a 2013 Scott Hilburn cartoon entitled “Wife of Pi,” which depicts a 4 figure seated next to a pi figure, telling their marriage counselor, “He’s irrational and he goes on and on.”

This attention comes to a head each year with the celebration of “Pi Day” on March 14, when, in the United States with its taste for placing the day after the month, 3/14 corresponds to the best-known decimal approximation of pi (with 3/14/15 promising a gala event in 2015). Pi Day was originally founded in 1988, the brainchild of Larry Shaw of San Francisco’s Exploratorium (a science museum), which in turn was founded by Frank Oppenheimer, the younger physicist brother of Robert Oppenheimer, after he was blacklisted by the U.S. Government during the McCarthy era.

Originally a light-hearted gag where folks walked around the Exploratorium in funny hats with pies and the like, by the turn of the century Pi Day was a major educational event in North American Schools, garnering plenty of press — visit this Google site to see the seasonal interest in ‘Pi.’ In 2009, the U.S. House of Representatives made Pi Day celebrations official by passing a resolution designating March 14 as “National Pi Day,” and encouraging “schools and educators to observe the day with appropriate activities that teach students about Pi and engage them about the study of mathematics.” This seems to be the first legislation on pi to have been adopted by a government, though in the late 19th century Indiana came embarrassingly close to legislating its value — see Singmaster’s article in the Pi Sourcebook (Entry 27) or the Pi Day talk by one of us.

As a striking example, the March 14, 2007 New York Times crossword puzzle featured clues, where, in numerous locations, a pi character (standing for PI) must be entered at the intersection of two words. For example, 33 across “Vice president after Hubert” (answer: SPIRO) intersects with 34 down “Stove feature” (answer: PILOT). Indeed 28 down, with clue “March 14, to mathematicians,” was, appropriately enough, PIDAY, while PIPPIN is now a four-letter word.

Pi mania in popular culture

There are many instances of pi in popular culture. Here are just a few:

- On September 12, 2012, five aircraft armed with dot-matrix-style skywriting technology wrote 1000 digits of pi in the sky above the San Francisco Bay Area as a spectacular and costly piece of piformance art.

- On March 14, 2012, U.S. District Court Judge Michael H. Simon dismissed a copyright infringement suit relating to the lyrics of a song by ruling that “Pi is a non-copyrightable fact.”

- On the September 20, 2005 edition of the North American TV quiz show Jeopardy!, in the category “By the numbers,” the clue was “‘How I want a drink, alcoholic of course’ is often used to memorize this.” (Answer: What is Pi?) [Because the number of letters of these words spells the digits of pi].

- On August 18, 2005, Google offered 14,159,265 “new slices of rich technology” in their initial public stock offering. On January 29, 2013 they offered a pi-million dollar prize for successful hacking of the Chrome Operating System on a specific Android phone.

- In the first 1999 Matrix movie, the lead character Neo has only 314 seconds to enter the Source. Time noted the similarity to the digits of pi.

- The 1998 thriller “Pi” received an award for screenplay at the Sundance film festival. When the authors were sent advance access to its website, they diagnosed it a fine hoax.

- The May 6, 1993 edition of The Simpsons had Apu declaring “I can recite pi to 40,000 places. The last digit is 1.” This digit was supplied to the screen writers by one of the present authors.

- In Carl Sagan’s 1986 book Contact, the lead character (played by Jodie Foster in the movie) searched for patterns in the digits of pi, and after her mysterious experience sought confirmation in the base-11 digits of pi.

Several more examples are given in the Pi Day talk.

With regards to item #3 above, there are many such “pi-mnemonics” or “piems” (i.e., phrases or verse whose letter count, ignoring punctuation, gives the digits of pi) in the popular press. Another is “Sir, I bear a rhyme excelling / In mystic force and magic spelling / Celestial sprites elucidate / All my own striving can’t relate.” (see Brian Bolt’s book, pg. 106). Some are very long (see Pi Sourcebook, Entry 59).

Sometimes the attention given to pi is annoying, such as when on 14 August 2012, the U.S. Census Office announced the population of the country had passed exactly 314,159,265. Such precision was, of course, completely unwarranted. Sometimes the attention is breathtakingly pleasurable. See this 2013 video or the Pi Day talk.

Poems versus piems

While piems are fun they are usually doggerel. To redress this, we include examples of excellent pi poetry and song. Below we present the first stanza of the much anthologised poem “PI,” by Polish poet Wislawa Szymborska (1923-2012), who won the 1996 Nobel prize for literature, from his published collection.

The admirable number pi:

three point one four one.

All the following digits are also just a start,

five nine two because it never ends.

It can’t be grasped, six five three five, at a glance,

eight nine, by calculation, …

Below we present the beginning of the lyrics of “Pi” by the influential British singer songwriter Kate Bush. The Observer review of her 2005 collection Aerial, on which the song appears, wrote that it is “a sentimental ode to a mathematician, audacious in both subject matter and treatment. The chorus is the number sung to many, many decimal places.” (She sings over 150 digits but errs after 50 places. The correct digits are given in the published lyrics.)

Sweet and gentle sensitive man

With an obsessive nature and deep fascination

For numbers

And a complete infatuation with the calculation

Of PI

The full text of these poems are given in a paper by the present authors.

Graphical representations of pi

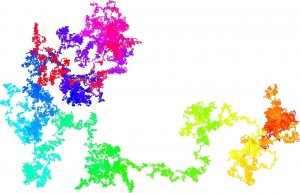

A fruitful new approach is to display the digits of pi or other constants graphically, cast as a random walk. For example, the first plot below shows a walk based on one million base-4 pseudorandom digits generated by a computer, where at each step the graph moves one unit east, north, west or south, depending on the whether the pseudorandom base-4 digit at that position is 0, 1, 2 or 3. The color indicates the path followed by the walk, colored by a standard hue-saturation-value scheme that produces a rainbow of colors.

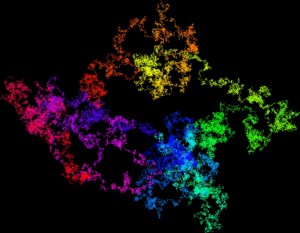

The next figure shows a walk on the first 100 billion base-4 digits of pi. This may be viewed dynamically in more detail online at the Gigapan site, where the full-sized image has a resolution of 372,224 x 290,218 pixels (108.03 billion pixels in total). This is one of the largest mathematical images ever produced and, needless to say, its production was by no means easy — see this paper for technical details.

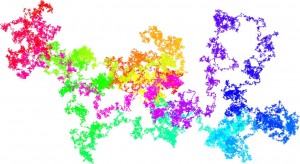

The above walk was on binary digits of pi. Here, for comparison, is a walk on 10 million base-10 digits.

Such techniques are used to study what is arguably one of the oldest unanswered questions of mathematics: Are the digits of pi “random”? (say in the specific sense that each decimal digit occurs, in the limit, 1/10 of the time, each pair of digits occurs 1/100 of the time, and so on). Sadly, we still don’t know the answer to this age-old question (and many others). But with the advent of modern computer technology, maybe the balance is finally tipping in favor of mathematicians. See this technical paper by the present authors, from which the above article is condensed and adapted (with permission of the American Mathematical Monthly) for details.

[Versions of this article also appeared in the Huffington Post and The Conversation.]

[Added 14 Mar 2014]: Pi Day 2014 has attracted more attention than ever before. Here are some press reports and related items of interest:

- This CNN article summarizes Pi Day celebrations in the U.S.

- This CNN article from Pi Day 2013 features Daniel Tammet, Hideaki Tomoyori, Chao Yu and others who memorize digits of pi.

- This UK Guardian article by Alex Bellos shows the many ways that the digits of pi have been transformed into art.

- This UK Guardian article, also by Bellos, draws parallels between Pi Day and literature.

- This Gigapan website enables one to interactively explore a random walk on the first 100 billion binary digits of pi.

- In this Scientific American blog, Evelyn Lamb describes the Pi prime-counting function.

- A Pi Day website is now online.